Visigothic History of Narbonne, Part 2 GB

The Septimanians versus the Toledans

When King Euric died, his empire included Aquitaine, the newly named Septimanie, and the vast bulk of Spain. His successor, Alaric II, lost Aquitaine to the Francs, losing his life in the battle that took place at the foot of the Montagne d’Alaric in 508. His son Amalaric was only 5 years old but survived under the regency of Théodoric the Great, the Ostrogoth, but Amalaric lost his own life when fighting to protect Narbonne from the Francs in 531.

Narbonne then lost its status as a Royal city and came under the jurisdiction of Barcelona, then Mérida and then Toledo, the Spanish Visigoths having taken their time deciding on a Spanish capital! Narbonne had a brief period of royalty towards Toledo between 567 and 573, when the town was ruled by Liuva, the Visigothic king from Spain, who held the official title of governer. After that, Narbonne held the right to rule the land of Septimanie - today’s Languedoc plus what is now Catalonia. There was a Visigothic mint at Narbonne, which influenced the main financial transactions at Toledo, so the Septimanians were in a strong negotiating position.

Toledo as it is today; the walls existed in Visigothic times. Luiva

In 587 Récared in Toledo converted to the Roman church, but the Narbonne Arians refused to convert. Their bishop, Athalocus persuaded several nobles to support him in open revolt against Recared. Gregory of Tours, the fanatical Roman Catholic chronicler, later said Athalocus “threw the churches into such trouble with his vain doctrines and false interpretations of the scriptures.” The revolt was was “quickly subjugated but humanely,” then Athalocus “took to his bed and died of spite”!

It’s thought Athalocus died of the plague, for it raged in Narbonne for three years, from 589 to 592. Many of the people escaped it by fleeing to the countryside, but nonetheless, it took ten percent of the population. Maybe the prospect of death focussed the minds wonderfully, for the two churches started to work together once more and there was a run of Councils in Toledo, attended by Narbonne bishops. After that, says Gregory of Tours, “the people of Septimanie abandoned their error and confessed the indivisible Trinity.” Oh yeah?

History tells a different story. Athalocus had declared he wanted to rally troops and put to death all Catholics. This was totally against the live-and-let-live principles of the Visigothic nobility and they did not hesitate to ask for help in quelling this Arian uprising, from the Franks. Récared interpeted this to mean the Arian Visigoths were ripe for conversion. He was wrong; Septimanie wanted to retain its Arian religion, but would not enter into religious wars. The Visigoths were not prepared to kill friends, allies and fellow traders over a religious principle.

Récared wanted the support of the Visigothic territories in Septimanie, but in the name of unity they had to convert to Catholicism. This they were not prepared to do. The one thing the Languedocians could not support was the persecution of the Jews, who had contributed greatly to making Narbonne rich. Now Recared was Catholic, he was issuing one law after another in Spain reducing the rights of Jewish people - who moved to Narbonne. Narbonne got richer - and Toledo got poorer.

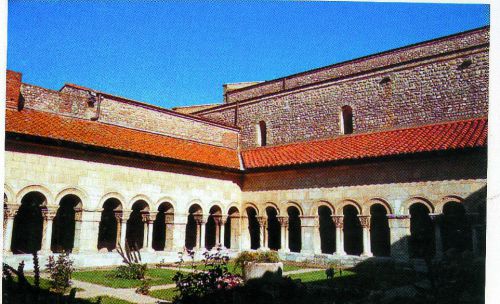

The only image we have of Recared. Elne - where the bishops remained resolutely Arian

The councils continued in Toledo. Arian bishops were established at Elne, Carcassonne and Maguelone. Elne was considered one of the seven cities of Septimanie. Maguelone had been the second church after Rome in the whole empire, and the first in France.

Argebaud was the bishop around 673, and is the most well-known. It was he who pleaded with the most Christian king Wamba, to cease the bloodshed at Nîmes after the rebellion of Duke Paul in 673.

Wamba’s story gives us a great insight into how things were at that time. He was called the king in spite of himself. He was the younger brother of Tulca, the Count of Razès, who had decided to retire to a monastery, so Wamba was elected as king of Visigothic Spain by the council. Wamba didn’t really want to be king. But he shouldered the yoke of responsibility willingly enough - and violently enough - in the end.

The independant Septimanian Visigoths were still in conflict with Toledo, resisting its Catholic rule which tended to back the Franks against the Arians and the Jews. The count of Nîmes, Hildéric, refused to submit to anti-Jewish legislation and proclaimed himself king of the Visigoths with the help of the bishop of Maguelone, Gumild. Maguelone at the time was the second church after Rome in the Christian world. Another ally was Reximir, the abbot of a monastery in his diocese, that Hildéric made bishop of Nîmes.

Hildéric was also supported by the abbot of Saint Baudile-de-Nîmes, Ranimire at Uzès, who appreciated the Jews for the business they brought to the city, including great merchant’s fairs, for which the merchants came along the Via Domitia and were protected by Saint Baudile, the patron saint of Ranimire’s great abbey. These three rebels, Hildéric, Gumild and Ranimire, raised an army in the mountains to the north of Nîmes, hoping to rally all of Septimanie to their cause.

Wamba entrusted Duke Paul, a Spanish-Roman of Greek descent related to the Royal family, with the mission to suppress the revolt of Nîmes, and gave him a large army. In 673 Paul arrived at Narbonne and occupied the town, in spite of the protests of the popular bishop, Argebaud. Having already persuaded the Duke of Barcelona to his side, Paul put his commanders in charge of the Pyrenean border, les Cluses, thus separating himself from the Spanish Visigoths. Wamba was away from Toledo, fighting in Gascony. It seemed to Paul that the time was right, that his star was ascending; he could get Septimanie for himself.

So Paul proclaimed that the election of Wamba was irregular and had himself elected king of Septimanie and Catalonia in Narbonne. Just to add an extra security, he was anointed which made him king by divine right and appointed by God. He used the crown that had once been given given to Nîmes by Récared. Did Argébaud crown Paul? It’s unlikely, for Paul accused him of supporting Wamba, but then let the matter drop for it would be better if the courageous Argébaud was on his side.

Meanwhile, Paul’s soldiers had to work for him for merely a promise of booty, and he wrote a challenging and defiant letter to Wamba.

Wamba asked the Franks for military help! So they both, the Spanish Visigoths and the Franks, wanted Septimanie . . . Wamba returned to Spain to gather more troops and then set out for Septimanie, saying; “It would be undignified to fear Paul supported by the Franks and the Septimanians. Their manner of fighting nowhere matches ours. The Septimanians have courage but it is second to that of the Goths.”

Armaggedon at Nîmes

Wamba and his men cut through the defenses at Les Cluses like a knife through butter, and Paul was shocked to realise he was not really defended by his men. He left Wittimir and some other Visigothic rebels in charge of Narbonne and retreated to Nîmes, but managed, en route, to get Béziers and Agde on his side. He had taken Argébaud, the bishop of Narbonne with him, because he didn’t trust him - but he should have done.

Wamba decided to attack Narbonne by land and sea. Narbonne suffered, but not much, for little resistance was offered. Wittimir was found by a soldier, hiding behind the statue of the virgin in a church, and that was the end of support for Paul in Narbonne.

Then Wamba proceeded to Béziers and Agde, but both towns were fiercely partisan and resisted him, so he continued to Maguelone.

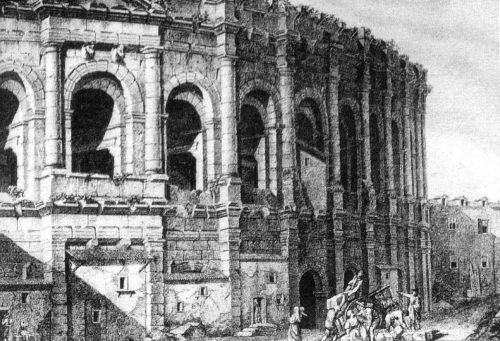

Today Maguelone is an island in an étang, for much of the region has silted up, but it may well have been an island in the open sea, with a causeway to the mainland, in the late 7th century. Wamba attacked using his boats that had followed him along the coast from Collieure. The bishop, Gumild, the supporter of Hildéric the Count of Nîmes, fled to Nîmes, stopping at Castelnau-le-Lez on the way. Now all the rebels were there at Nîmes. The famous amphitheatre had been converted to a village by them, built on the sand where the Romans once played their “popular” games. The Septimanians had fortified the walls and dug a huge ditch around it, making the whole place into a fortress.

The arena at Nîmes as it was in the 19th century; a whole population lived there.

It would have looked similar in Visigothic times.

Wamba attacked at daybreak on 31st August, 673 with 30,000 men. The fighting was vicious, bloody and brutal. Wamba went to any lengths to secure a victory, although he himself was camping some dozen kilometres away to intercept any Frankish armies, for by then he wanted to deny their help and make the whole victory his.

Wamba sent for fresh troops that arrived at Nîmes in the early hours of the morning of 1st September after a forced march through the night. Duke Paul was beginning to lose courage but managed to rally some extra Visigothic troops. The Visigoths fought like lions and the slaughter continued throughout the day. The next day the Spanish Visigoths under Wamba started pillaging - a rumour went round the Septimaniens had buried treasure underground within the amphitheatre; but none was found then, nor has been found since. (In those days, the men were paid with booty.)

The rebels were trapped in the Roman amphitheatre, and Paul in desperation begged Argébaud to intercede, and plead forgiveness from Wamba - as one Catholic to another perhaps? Wamba, victorius, was not prepared to forgive so quickly - the case had to be made that Septimanie was ruled from Toledo, and Toledo would stand no nonsense. His troops started killing randomly, sometimes murdering wounded men who were already covered in blood.

Duke Paul was captured and offered his life in return for an end to the killing of his men. He was executed and his kingdom of Septimanie-Catalonia ended its brief life. Hildéric, who started the rebellion, had disappeared; no one knows if he was killed in battle or if he fled.

The much-loved Narbonne bishop Argebaud, perhaps inspired by Paul’s courage at the end, threw himself at the King’s feet, still wearing his bishop’s robes, to offer help to his compatriots, that “the citizens pardon the citizens”. He pleaded for the fighting to stop and for clemency for those people who were left. His words were daring. “Prince, you have gravely sinned against Heaven and against us. Your crime is atrocious and unforgivable. But still, your pity and compassion could end this blood-bath. Order your troops to stop this massacre, and save Nîmes and its people from destruction.”

Wamba eventually relented, but still insisted on parading his troops around the battleground in a flamboyant display, which met with silence from Argebaud’s citizens. Wamba pillaged the houses of the dead, collected the goods of Paul and those leaders who had died and left instructions for Nîmes to be re-built. He was, after all, a good Christian king.

Then he went hunting.

He wounded a doe which fled through the forest, an arrow in her shoulder. The doe led him to the cell of the hermit Gilles. Gilles had arrived on a raft from Greece and lived in the forest on the milk of the hind who looked after him. When Wamba saw the reunion scene between the old hermit and the doe, he was overcome with remorse. It’s said Wamba repented of all his sins then. He regretted his brutality, presumably committed in the name of a saviour who was a God of Love.

The conversion of Wamba

The conversion of Wamba

In those days, financial gifts to churches neutralised sins. Wamba gave Gilles a tract of land on which to found a monastery, and money to build it too. This Gilles did, and also became a doctor. This place, just to the south of Nîmes, is now known as St. Gilles-du-Gard and has a beautiful 12th century church, decorated with carvings of the life of Christ. Pilgrims still go there to pray to Saint Gilles to heal them of their illnesses.

Gilles and Wamba have since been canonised by the Catholic church.

A revealing detour

Then Wamba and his army set off from Nîmes for home. He continued down the Via Domitia to Narbonne, where he put the minds at rest of those Narbonne people who would rebel. Wamba was done with war. Later in that year of 673, Wamba stopped for a while at Fitou and Elne, then took the castle of Collioure, and proceeded to Spain. Or did he? It could have been his army went home without him. For it says on an Internet web-site;

On the 6th September 673, after a victorious campaign in Septimanie, Wamba separated himself from his army at Canaba, on the banks of the river Orbieu, near Narbonne. He and his suite continued on a route that was “not the Via Domitia”, to return to Toledo across the mountains. If Wamba had followed the valley of the Orbieu, he would have gone through what is now Ornaisons, Ferrals, Fabrezan, Ribaute, Lagrasse, St. Pierre, St. Martin des Puits, Durfort, Lanet and Albières. The river finishes at the Etang du Paradis; one continues then to Arques, Serres, and Rennes-le-Château, the great Visigothic city of Rhedae.

Why did Wamba go there? To arrange future sanctuary or support? Was he looking for treasure? Had he believed the treasure was at Nîmes, buried under the amphitheatre, and now realised its possible hiding place was at Rhedae?

The beginning of the end in Spain

After his triumphant return to Toledo, on 1st November 673, Wamba made a new law saying that all men in the kingdom were obliged to always support the king against rebellions or invasions; if they refused, their goods would be seized. But it did him no good, for all was not well at home in Toledo, civil war was threatened and after a while Wamba was deposed. By 680, the political situation was in crisis. The anti-Jewish laws, plunged the country into a series of rebellions.

The most severe laws against the Jews were under the next king, Erwige, who put forward 28 anti-Jewish laws at the 14th Council of Toledo in 684, and his successor, Egica, brought in even more severe legislation in 694 against the Jews in Spain.

However, the king Egica felt honour bound to exempt Septimanie from these new regulations; the Jews were, after all, defending the Visigothic kingdom against the northerners and in Narbonne the work and contribution of the Jews there brought great prosperity. He resolved the situation; being Roman Catholics in Toledo, they were obliged to restrict the rights of Jews; yet Egica agreed a statue of exception for those Jews in the Visigothic kingdom who did not live in Spain.

For Septimanie this was a triumph which overturned anti-Jewish legislation taken by the Councils of Toledo as long ago as 589. This led to two sorts of Jews in the Visigothic kingdom; those in Spain were veritable slaves, without right of property ownerships, who were continually being forced to convert under pain of exile or separation from their families. No wonder the Toledo Jews later welcomed the Muslims with open arms. But the Jews in Septimanie benefited from liberty and tolerance under the protection of the Visigothic nobility and also their bishops. Meanwhile, the duke of Narbonne, aided by the Jews, suceeded in resisting yet another invasion by the “Aquitainians” - the Francs.

Then, by 647 under Othman, the Muslims conquered the old Roman lands of Africa and Morocco. By 650 the Arabs were the masters of north Africa, having taken it from the Romans and Vandals who controlled the lands around Carthage - the grain field of Europe.

In Spain the king after Egica was Witiza, but there was much intriguing and at one time Witiza fled for refuge with Agilo. Agilo was the governer of Tarragon and of Septimanie, and had started to intrigue with the Muslims who since 698 were occupying what is now Morocco, the old Roman kingdom of Mauretania. The Muslim general was called Mûssa, and it’s said that he and his men could see the shores of Spain in the distance, from where the wind blew the opulent smell of orange blossom. They wanted Spain.

Mûssa agreed to trade with Agilo and persuaded Olian, the governor of Ceuta, to provide a safe haven for ships. By this means news of the Visigoths could be gained from traders and seamen, and spies sent to Gibraltar from Ceuta reported back that the land was rotten and ripe for invasion.

After the death of Witiza in 710, his widow and his brother Oppa, the archbishop of Seville, wanted to elect Agilo. But the Visigothic elders refused to let their hand be forced and elected Rodéric, the Duke of Cordoba, as king. Rodéric grabbed the crown with both hands. Agilo and his partisans naturally took exception to this, but their hands were tied; they had a deal with the Saracens. Their trading with Ceuta could continue and the safe passage of Agilo was guaranteed.

Mûssa chose a time when Rodéric was occupied fighting the Basques in the north. He sent his lieutenant, Tarîk ben Zyiad to attack the peninsula at the foot of the huge rock which has been called Gibraltar ever since. “The rock” is shaped like a tear-drop that hangs towards Africa. From Gibraltar to Ceuta is only 14 miles.

Rodéric, travelling in a litter, and his army were rushed into forced marches in order to meet the Berber infantry of 7,000 men. He found that the partisans of Agilo had disappeared. One could not blame them.

Rodéric was either very self-confident or very stupid, for he took little part in the fighting. He sat nonchalantly on a chariot made of gold and ivory. Later, nothing of him was recovered but a diadem, a robe embroidered in gold, and the body of his horse. Maybe this incident was what led to the theory that the Visigoths lost Spain because of their laziness and decadence.

Tarîk ben Zyiad was victorious in this battle near Medina Sidonia in on 19th July 711 on the banks of the river Guadalete. The Visigoths fled north back to Barcelona and to Languedoc.

Many Jews stayed in Spain and welcomed the Muslim invaders, by whom they were better treated. Jewish commerce and trade were encouraged, and so too, was Jewish thought. Cordoba and Toledo had large Jewish populations and became centres of culture and learning. Toledo was considered to be an intellectual centre - and some Visigoths from Septimanie attended colleges there well into the 9th century.

The Saracens on the scene

The Spanish Visigoths with their Roman Christianity were persecuting Jews in their domains and so when the Moors overran Spain in the years between 711 and 718, the Jews welcomed them. If Récared had not converted, and had not made restrictive laws against the Jews, he might not have lost Spain. After the Muslims arrived, many Jews were given administrative posts in Spanish cities. Toledo, with the Jewish and the Moslem imput, became a great seat of learning.

Meanwhile, in Narbonne, under Count Gilbert, the people put the town and the region in a state of defence. The Saracens arrived and besieged Narbonne late in 719. The forces of the Visigoths, small in numbers but big on courage, resisted “to the last limit of human possibilities”, making the Saracens pay dearly for every scrap of ground gained.

Why on earth didn’t the Franks offer to help at this time? Because the Visigoths had previously refused to become Catholics?

After 28 days Narbonne was taken. Men were killed by the broadsword and women and children were taken as slaves into Spain. Then the town was pillaged for 3 days. The Muslims took away seven statues of massive silver that had ornamented Rusticus’s cathedral.

Then Narbonne was occupied for 40 years, from 719 to 759.

The Muslim administration was stable. A wali answering to Cordoba supervised the Visigothic count. Arab historian Mohammad al Zhori wrote; “Arbuna is a grand town. It is the extreme point of the Muslim conquest in the land of the Franks. The town is traversed by a great river, the greatest in Francia. A great bridge spans it; one finds there markets and houses; one uses it to cross from one part of the town to the other. The boats come up the river from the sea to this bridge.”

That bridge is still there, originally the Roman brIdge of seven arches. You can see the middle arch of it if you go down to the canal near where it goes under the rue du Pont des Marchands. The other arches are now hidden in the foundation of modern buildings.

What was life like under the Muslim occupation? The Muslims were lenient as long as the people understood they were in charge. Christians, including Arian Christians, were considered by the Muslims to be “a people of the book,” that is, the Old Testament. The conquerors were only a handful of administrators and soldiers, with their families. The occupation was delicate, “always menaced by the return of the Dukes of Aquitaine or the Frankish Kings”; that is, the Catholics.

The Saracens “left in place a Visigothic count”, so presumably Gilbert survived before Milon took his place, and the Muslims liaised with the Visigoths. The cathedral built by Rusticus was changed to a mosque for a while. We believe the Arian christians were left in peace and even had bishops, but there is no evidence. Gaps in the lines of bishops found in most churches and cathedrals have been found in other parts of Gaul; it’s thought the Franks destroyed all records, calling the Arian bishops collaborators with the Muslims.

Meanwhile, the old Spanish Visigothic towns of Toledo and Cordoba, under Muslim rule, were allowed to retain their bishops. The local religion was not squashed, as it was in “Francia.”

Arabs, Arians and Jews

The new master of Narbonne, or wali as he was called, had the name of Al Samh and he went off in 721 to besiege Toulouse, then Carcassonne in 725. Carcassonne was later released by Charles Martel in 732, presumably after his great battle at Poitiers, where he managed, apparently with just one battle, to turn back the Muslim tide and save France from a heretical future, as they insist on telling us. It was then that Carcassonne became French, having been Visigothic from 418 to 725, then Muslim till 732. You notice, they never gave it back to the Visigoths from whom it had been taken only 7 years before.

Although the Franks were apparently fighting the Moors, they were still trying to take Septimanie from the Visigoths. They had an image of themselves as fighting all heretics, be they Arians, Jews, and Muslims. Because the Jews and the Visigoths both never believed in Jesus’s divinity, they were lumped together and the names “Jew” and “Goth” were used indiscriminately. The Koran, the Muslim holy book, tells us quite clearly that Jesus was thought of by these Arab people as a prophet, and also tells us he did not die on the cross.

This would not have seemed so strange, however, to the Arian Visigoths living in Narbonne. The official history of the Jews in Narbonne, as recounted by their synagogue, says; “Historians agree that the Jewish population in Narbonne increased in Roman times. The Jews played an intermediary role for international trade with the East. The Hebrew colleges in Narbonne were internationally respected.”

In spite of various attempts by the Franks, Narbonne with its Muslim, Jewish and Visigothic leaders was holding out. “Later their presence reinforced the influx of their compatriots from across the mountains who had been taking refuge from the Carolingians.” These Visigoths came from Carcassonne, which the Muslims had taken in 725 and the Franks taken in 732, and many of them would have come from Rhedae, today’s Rennes-le-Château. The Visigoths were welcome in Muslim Narbonne.

However, there were continuing skirmishes, in Septimanie, between the Franks and the Visigoths, the Franks and the Arians, the Franks and the Muslims. (See our article about Charles Martel.)

The Franks came to Narbonne in 752, under Pepin le Bref, and started a long siege. It was supposed to be against the Muslims, but they were quite interested in getting the Visigoths out and the Jews. They were determined to get Narbonne. It did after all control the vast territory known as the Narbonnais.

Narbonne was wealthy, thanks to the enterprise and energy of the Jewish population there, who did much to increase and support Mediterranean trade in Septimanie. The Jews had lived in Gaul since pre-Christian days.

The Jews developed banking and credit, using their system to gain spices, silks, brocades, papyrus, indigo for dyeing, and oil. They spoke Arabic, Persian, Greek, Latin, Frankish, Spanish and Slavonic languages. They returned from their trading carrying eunuchs, child slaves, brocades, furs and swords. They established trading routes and banking houses all over the East, sometimes using camels as beasts of burden, and paying with Arab gold coins.

They were accepted and valued in Gaul. Narbonne had a large Jewish community that, in the 6th and 7th centuries, enjoyed cordial relationships with the Arian Visigoths, whose doctrines did not conflict so much with Judaism. The Jews were 4% of the population of 25,000. Mixed marriages were common. Found at Narbonne was a funeral inscription dated 688 - 9; there was plague at that time as mentioned above. Paragorius, son of Sapidus, buried his three childen, called Justus, Matrona and Dulciorella. On the stone was carved a Menorah and an inscription saying “Paix en Israël.” This would not have been allowed for a persecuted people.

Other evidence of the beneficial links between the Visigoths and the Jews was the Salic Law of inheritance. Both the Franks and the Visigoths, independently, adhered to Salic law as a basic framework, derived directly from the Jewish Talmud. And yet, the official Jewish history, as disclosed by the synagogue at Narbonne today, starts to differ here, for it makes no mention whatsoever of the Septimanian Visigoths who defended them so well. “The occupation by the Saracens lasted 40 years! Pepin le Bref made the conquest of Narbonne and it’s claimed that the Jews of the town served as intermediaries between the temporary power of the muslims and the Carolingians.”

So what really happened at Narbonne, in those days of the mid 8th century, so that Narbonne eventually became French?

See Part 3, for the amazing story of Guilhem of Gellone